The first months of the Seatizens Bio-Murals project have been a deep dive into the Baltic-both literally and metaphorically. Artists and scientists began by building a shared language: exploring how knowledge of the sea, its organisms, and its materials can translate into visual and tactile artistic forms.

credits: Patrycja Orzechowska

Reconnecting with the underwater past

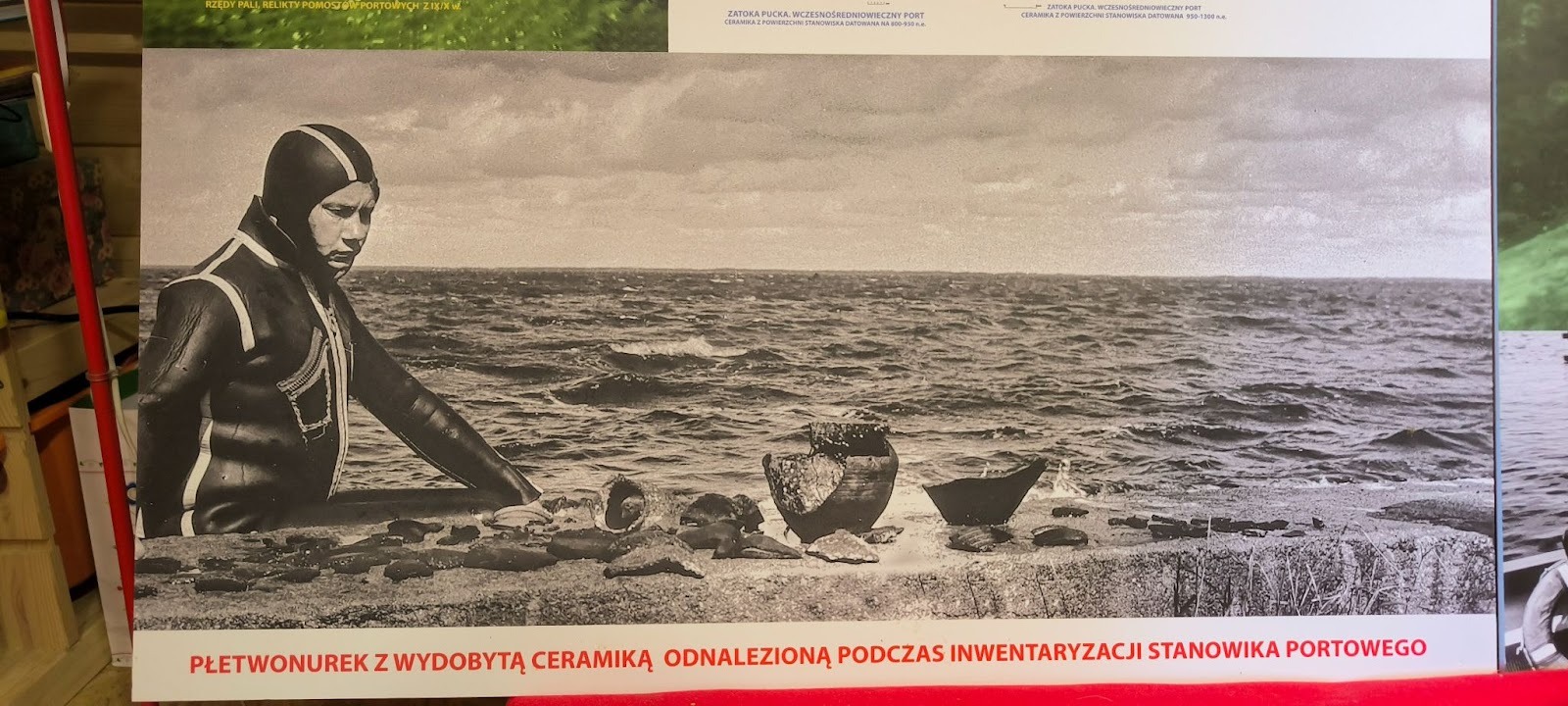

The project’s first meeting took place in Swarzewo, where the team met retired marine archaeologist Wiesław Stępień and his wife Alicja Kaźmierczak-Stępień, who live in a historic 18th-century fishing cottage overlooking Puck Bay. Wiesław, once a diver and archaeologist, took part in underwater excavations in the 1970s that revealed remnants of Stone Age settlements beneath the bay.

Back then, divers were lowered in metal cages, documenting the seabed by hand at a 1:1 scale. When the same area was remapped decades later with 3D scanners, the error margin between human and digital mapping was barely ten centimetres. The difference, as Stępień explained, is that “the human also records the depth, the texture, the detail of the place”-a perspective technology cannot replace.

The team learned that the low salinity of the Baltic makes it a unique archaeological site: the absence of wood-boring marine snails means shipwrecks remain astonishingly well preserved. These insights opened a new way of looking at the sea-not only as a fragile ecosystem, but also as a living archive of human and natural history.

credits: Patrycja Orzechowska

credits: Patrycja Orzechowska

From mussel shells to bioplastics

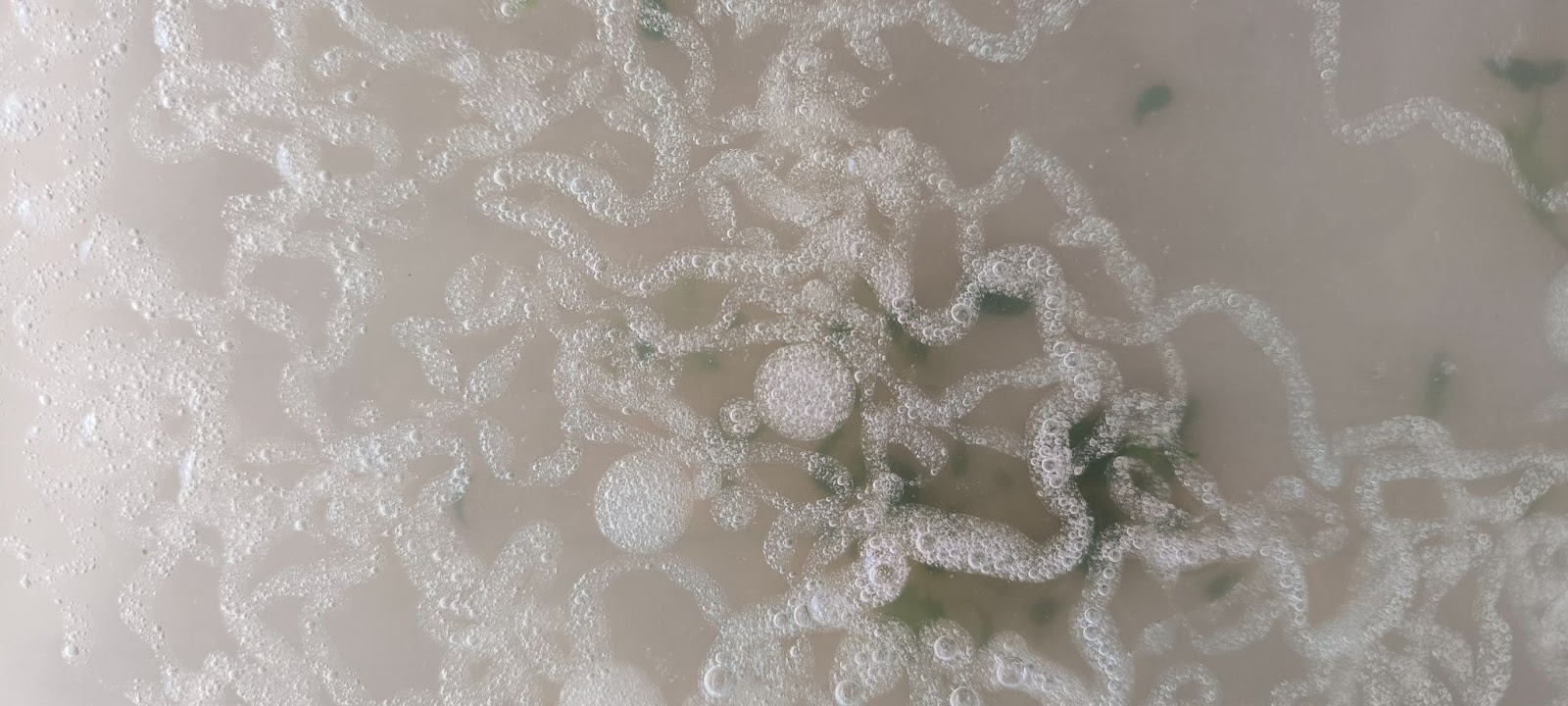

The second gathering was a biomaterial workshop, where artists experimented with substances derived from marine resources. Together, they produced prototypes of lime-based plasters and bioplastics using calcium carbonate from mussel shells, sodium alginate from bladderwrack, and agar from Furcellaria lumbricalis. The participants tested pigments made from crushed brick, iron oxide from shipyard metal dust, and natural marine residues.

Beyond the chemistry, the session explored how material experimentation can foster ocean literacy-transforming abstract ecological ideas into tangible, sensory experiences.

credits: Patrycja Orzechowska

credits: Patrycja Orzechowska

Meeting the scientists

Next, the artists visited the Institute of Oceanology of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IOPAN) in Sopot. Four scientists joined the project, specialising in carbonate organisms, algae, and marine ecology. The session became a lively exchange about life in the Baltic, the functions of marine organisms, and the challenges the sea faces.

From these conversations, three thematic groups naturally crystallised, each rooted in a different layer of the Baltic’s living and historical landscape. Patrycja, working alongside Ania and Małgorzata, delves into the world of mussels and shells - organisms that are far more than decorative remnants cast ashore. Shells are biological archives of the sea: they record changes in temperature, salinity, nutrients and pollutants, storing decades of ecological information in their layered calcium carbonate structures. Mussels, as powerful filter-feeders, continuously clean the water column, removing suspended particles and helping to stabilise fragile marine ecosystems. In a warming, increasingly diluted Baltic - where salinity has been declining for decades and temperatures are rising faster than the global ocean average - their role has never been more essential.

Blanka and Jacek, together with Agnieszka, turned toward algae, one of the most underestimated pillars of the Baltic. Seaweeds such as Furcellaria lumbricalis and bladderwrack create habitats for countless species, producing oxygen, capturing carbon, and forming underwater forests that anchor entire food webs. Their group embraces Widlik - a symbolic “hero species” designed for children’s workshops - to tell the story of resilience, ecological interconnectedness, and the delicate balance threatened by climate-driven changes, eutrophication and coastal development.

Jakub’s focus follows a different current: the archaeology and memory of the Baltic, shaped through his ongoing collaboration with Wiesław Stępień. Here, the sea becomes both an archive and an active agent, preserving human traces that in saltier oceans would have long disappeared. The Baltic’s low salinity prevents the spread of wood-boring molluscs, turning its depths into an extraordinary museum of shipwrecks, tools, and submerged settlements - silent witnesses of thousands of years of human presence.

Supporting all three threads, Paulina weaves together scientific knowledge and artistic intuition, ensuring that insights flow freely between disciplines. These emerging collaborations - grounded in curiosity, material exploration, and a shared urgency to understand a sea in transformation - form the foundation of the Seatizens approach: a space where art and marine research meet, challenge each other, and co-create new ways of seeing and caring for the Baltic.

Biomaterial laboratories at HUBA

The next step brought artists and scientists together again - this time at HUBA, an ecological education centre at 100cznia in Gdańsk Shipyard, where the project’s biomaterial laboratory is based.In this reverse encounter, marine researchers swapped pipettes for hammers, plunging - sometimes literally - into the tactile process of breaking down mussel shells, grinding pigments from bricks and iron rust collected in the shipyard, and stirring thick gels of alginate and agar extracted from Baltic seaweeds. Instead of analysing samples under microscopes, they experienced the materials through weight, smell, texture, and resistance.

This hands-on exchange blurred the boundaries between scientific protocol and artistic intuition. Scientists offered insights into the structural properties of biominerals, the ecological roles of shells, and the chemical transformations driven by changes in salinity and temperature.

credits: Patrycja Orzechowska

Listening to Brzeźno

As the project evolved, the team turned toward Brzeźno, the seaside district where the murals will be created. The team met with housing cooperatives, local caretakers of the built environment, who offered a pragmatic perspective on the selected walls, maintenance issues, and how murals could become catalysts for neighbourhood pride. At the District Council of Brzeźno, the project found an unexpectedly strong ally. Council members not only assisted with logistics but became active partners, connecting the artists with the senior club, the youth centre, and local historians - people whose knowledge of the district is rooted not in documents but in lived experience.

Together, they identified three walls for the murals - from an initial list of thirty - representing different parts of the neighbourhood. Conversations with residents revealed stories, which will inform the visual and narrative layers of the biomurals to come.

credits: Patrycja Orzechowska

Materials, memory, and the next phase - a step towards ocean literacy

In recent sessions, the team reviewed the first batches of material samples, focusing on shell-based lime plasters and natural pigments. Tests continue with brick dust, iron rust from the shipyard, and crushed mussel shells - seeking durable, low-impact solutions for outdoor works.

During search for local voices and hidden narratives, the team met Małgosia Reinholz, a collector of seaglass and storyteller of the Baltic shore, known for transforming pieces of glass shaped by the waves into delicate compositions. Małgosia’s practice bridges archaeology, ecology and everyday observation: her finds - fragments of nineteenth-century bottles, old industrial containers, apothecary glass, remnants shaped by decades of salt, sand and waves are tiny time capsules washed ashore. Each piece is both waste and witness: an object that once circulated through human hands, now returned by the sea in softened, sculptural form.

Her work introduces an important strand to Seatizens: a tactile, accessible way of reading the coastline, one that connects beachcombing with environmental awareness and alternative forms of slow, local tourism. Unlike traditional archaeological diving or laboratory-based research, collecting seaglass invites participants of all ages to engage with the Baltic physically, attentively, and imaginatively. It becomes a form of citizen sensing, where the beach itself is an archive and every found object opens a story.

Małgosia will lead the first open workshop of the project, combining a guided walk along the Brzeźno shoreline with hands-on creation. Participants will gather seaglass, ceramics and driftwood, and then incorporate them into small artworks that later inform and feed into one of the Seatizens biomurals. The workshop acts as a bridge between the archaeological narratives explored earlier, the project’s focus on marine materials, and the lived, sensory relationship people have with their coastline. It invites the community to perceive the Baltic not only as an ecosystem under pressure, but as a partner in shaping stories, aesthetics and collective memory.

credits: Jakub Goździewicz